an excerpt from Jung and Sex...

"Jung’s main concern was to investigate sexuality primarily for its spiritual aspects and numinous meanings (1961/1989, p. 168), but he also believed in the importance of understanding its instinctual and physical aspects. Jung was trying to move psychology beyond the predominant reductionistic views of his time, attempting to expand the cultural and psychological meaning and value of sexual phenomena. This is an aspect of his legacy, however, that is rarely recognized.

"He believed many disorders affecting patients were mostly unconscious and 'unsuccessful attempt(s)' to cure themselves (1939/1966, p. 46) and he attacked moral establishments for placing blame squarely on individuals for their sexual problems. He also challenged early psychological theories and medical science that did similar injustices to sexual complexity. Jung’s views, particularly about Freud’s fixed theories of sexuality, more closely match many modern perceptions now, although Jung is seldom credited for challenging these ideas in such a progressive way at the time. Nearly a century later, there is still a need for treatments that recognize how symptoms can actually be valuable expressions of unconscious situations.

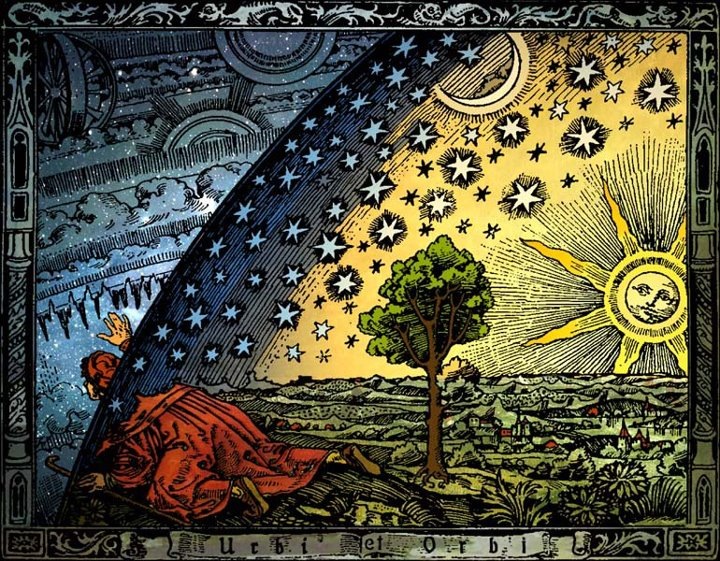

"Despite our understanding that many complex sexual issues generally have larger mysteries at their roots, large numbers of patients turn first toward medical providers or pursue various superficial solutions. This leaves many patients in the dark after various treatments, medications, and self-help methods fail. Cultural taboos and lack of social awareness remain harsh impediments to sexual expression. Many are unconsciously driven by splits between competing demands and they lack a path to awareness and integration. Many individuals require treatments that elucidate and address the complexities and conflicts unconsciously manifested in their symptoms. Jung detested the victimization of patients suffering from instinctual and unconscious problems, because it left them to struggle in the dark with no one in their environment helping them to understand or solve them (1939/1966, p. 46). He considered this a direct failing on the part of the medical community, science, and the culture.

"When working with patients with sexual concerns, I ask patients in the grip of an overwhelming attraction or compulsive erotic need, 'What makes these feelings so strong?' Their voices echo themes of connection, disconnection, uncertainty, emptiness, shame, anger, confusion, joy, liberation, and hunger. Culturally and clinically, how can we create space for Eros’ many ways of speaking? How can we unveil the mystery behind various symptoms and serve the real needs that live under the surface needs being expressed? How can we learn where Eros lives for the patient, how the symptoms serve, and discover what fuels these diverse expressions? Even in our modern age, much remains mysterious and concealed about our personal sexual struggles and expressions." Jung and Sex: Re-visioning the Treatment of Sexual Issues, p. 121.